In the United States, Latinos are the nation’s largest and fastest growing ethnic minority group. As their population spreads throughout the country, they diversify the culture of the communities which they encounter. It wasn’t always this way though, the original purpose for being here trails back to their migration patterns in rural cities in states like Iowa. During the farm crisis in the 1980’s, transnational corporate management decided to expand meat packing plants, creating a vast amount of jobs for the city’s population (Flora and Tapp 278). Granted that there were some adults willing to fill the jobs, the rural cities did not have enough workers for the companies to function properly due to the aging population. As a result, a major labor shortage sparked within the meat packing plants that survived on low-skill labor. In order to fulfill this shortage, companies searched for foreign help as a way to ensure that they do not lose profits. So, this massive amount of jobs available created a “pull” of immigrants, especially from Mexico, to travel thousands of miles away from the families to fill the available jobs. Although the community’s political values contradicted the current immigration status, Latinos are the biggest contributors to the survival of rural Iowa due to the fulfillment of necessary jobs, the continuity of the local economy, and the cultivation of diversity in a mainly white society. A perfect example of this complex immigration process is within the town of Marshalltown, Iowa and its large Hispanic population. Throughout the following research, I will describe the history of Marshalltown to explain what jobs Latinos came to fill, other ways they earn money, and how their perseverance to stay improved the economy of Marshalltown.

Marshalltown, Iowa

Marshalltown is a very small city located in the middle of Iowa (as illustrated in picture 1) and its population was primarily Caucasian, just like many of the rural towns in Iowa. For most of Iowa’s history, rural cities mainly consisted of Caucasian, Anglo, and Christian residents. These demographics of the town changed dramatically a decade after the farm crisis. During the 1990’s, “Marshalltown’s total population was 25,178 of whom 248 (0.9%) were Latino but in 2000, the total population was 26,009, of whom 2,265 (12.6%) were Latino” (Grey 364). After just 10 years, the Latino population grew enormously by almost 10 times and it keeps on increasing every year. With the increased amount of immigrants present, the town encountered a shift in its culture never seen before. Since many members of the community never dealt with such diversity in their rural environment until now, a lot of misconceptions flourished such as immigrants coming to take the town’s jobs, not paying taxes, and the tendency to demonize Mexicans as inducing drug use and smuggling meth from Mexico (Flora and Tapp 291). Due to these misconceptions, racism was common between the locals since they were not completely aware of how to deal with the sudden change of demographics. As the years passed on, more Latinos appeared in public sectors (as illustrated in Picture 2) to represent and encourage the community despite the racism present in the town. Hence, the history of Marshalltown reveals that Latinos are now a big part of the community and they do not plan on leaving.

Clothing display during the annual Latino Heritage Festival

Since Latinos contribute to a large portion of the demographics in Marshalltown, my research analyzes how their presence impacts the economic status of the town. There are a lot of studies done on the Hispanic footprint in small rural cities, but my research focuses on Marshalltown, Iowa. My conclusions may not contribute much to the broad implications of Latinos around the country, but it will cover a new angle to the topic by investigating a city that was primarily Anglo but then embraced diversity due to the large migration. The data for this paper is based on researchers gathering information from Latino participants and statistics on renown sources like the United States Census Bureau.

During the farm crisis, Marshalltown’s companies would have suffered from bankruptcy since too many jobs were left empty. This complication arose from the town’s aging population, dropping birth rates, and high school graduates leaving for bigger cities (Hotek 187). Due to the lack of employees, the town’s economy headed towards its demise since companies and stores struggled to stay financially afloat. It wasn’t until Latino immigrants arrived in the town and filled the jobs, providing an instantaneous economic boost for the local companies. Inside of the town lies the Swift Company, the third largest pork plant in the world, which employed the majority of these immigrants; in fact, 56% of the workers were Latino by the end of 1998 (Grey 368). Once the immigrants arrived in town, the meat packing plant took the majority of them since a lot of their positions consisted of low-skilled jobs. Although the company produces major profits now, they heavily depend on Latinos to succeed. During the analysis of the workforce in Marshalltown, it is clear that the jobs necessary for the economy to strive are filled by Latino immigrants; therefore, without them, the town would likely suffer another economic crisis similar to that of the farm crisis.

Jobs in the meatpacking industry provided some income for Latinos but the jobs were too dangerous, so they later resorted to other ways of earning money. The expansion of meatpacking plants removed the need for professional meat cutter resulting in the need for low-skilled workers. Subsequent of these management changes, Latinos fit the requirement since they are non-English speakers and their skills in management are low. However, the large Hispanic population in town sparked a new way of making money: entrepreneurship. According to local realtors, some [Latinos] buy homes, some open shops and restaurants, and some learn English and find jobs outside of the packing plant (Grey ). Although they didn’t speak English, Spanish is enough for them to use the money earned from their previous work and build a small shop in their neighborhood (as illustrated in picture 3). Due to the harsh working conditions in a packing plant, Latino’s entrepreneurship leads them to build a business as a way to earn money in a safer manner.

Latino entrepreneur and his small store

In rural Iowa, specially in Marshalltown, Latinos are the major contributor to the economic stability of the town after their large immigration due to the farm crisis in 1980. Once here, their immigration provided workers for the companies to survive financially, the economy to bloom as a result of their entrepreneurship, and a permanently diversified community mixed with the previous Anglo residents with the new Latinos. Therefore, it is important to set aside the political differences and embrace the diversity for the future success of any community in Marshalltown and the rest of the country.

Works Cited

Text Sources

Flora, C. B., Flora, J. L., & Tapp, R. J. (2000). Meat, Meth, and Mexicans: Community Responses to Increasing Ethnic Diversity. Community Development Society. Journal, 31(2), 277-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330009489707

Grey, Mark A. “Unofficial Sister Cities: Meatpacking Labor Migration Between Villachuato, Mexico, and Marshalltown, Iowa.” Human Organization, vol. 61, no. 4, 2002, pp. 364–376., doi:10.17730/humo.61.4.8xhdfg6jggqccb2c

Hotek, D. R., & Baker, P. L. (2004). TOMORROW’S INDUSTRIAL WORKERS: A CAREER AND TECHNICAL SKILLS ASSESSMENT OF RECENT MEXICAN IMMIGRANTS IN RURAL IOWA. Race, Gender & Class, 11(3), 127. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/218810326?accountid=7379

J., B., & Cordero-Guzmán, H. (2007). Latino Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship in the United States: An Overview of the Literature and Data Sources. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 613(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207303541

Image Sources

“Legacy Homepage.” U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, dod.defense.gov/Photos/Photo-Gallery/igphoto/2001311426/.

Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, zh-min-nan.wikipedia.org/wiki/tóng-àn:Map_of_Iowa_highlighting_Marshall_County.svg.

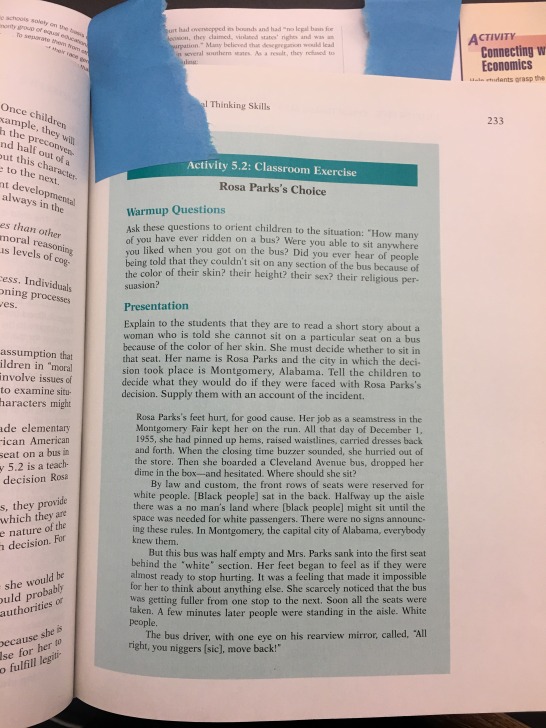

Similar to textbooks, museums tend to be culturally insensitive. Even with the best intentions to not water down history while still being compassionate towards the people impacted, they fall short when people outside of that demographic are in charge of content. I initially thought the African American Museum was ran by black people, and it is. Two out of the six staff members are black. The curator just so happens to be one of the four white people listed on the faculty page. However, I knew already knew this. It was obvious when I came across a piece of lynching rope incased in glass. For some reason the curator thought that was an important artifact that needed to be preserved. I thought it was quite triggering and offensive. This highlights the lack of compassion needed for multicultural education and an equitable pedagogy. This type of insensitivity and ignorance is commonly found in textbooks as well. Within a book designed to help teachers teach social studies to elementary students, I found an exercise about Rosa Parks. The creator of the lesson plan had gone out of their way to tell the “child-friendly” version of the bus story, yet the n-word was spelled out and included.

Similar to textbooks, museums tend to be culturally insensitive. Even with the best intentions to not water down history while still being compassionate towards the people impacted, they fall short when people outside of that demographic are in charge of content. I initially thought the African American Museum was ran by black people, and it is. Two out of the six staff members are black. The curator just so happens to be one of the four white people listed on the faculty page. However, I knew already knew this. It was obvious when I came across a piece of lynching rope incased in glass. For some reason the curator thought that was an important artifact that needed to be preserved. I thought it was quite triggering and offensive. This highlights the lack of compassion needed for multicultural education and an equitable pedagogy. This type of insensitivity and ignorance is commonly found in textbooks as well. Within a book designed to help teachers teach social studies to elementary students, I found an exercise about Rosa Parks. The creator of the lesson plan had gone out of their way to tell the “child-friendly” version of the bus story, yet the n-word was spelled out and included.